This article traces the Janjaweed’s origins, the pathway from Janjaweed to RSF, and the financing, recruitment, and foreign ties that sustain them. It looks beyond a purely human-rights frame to examine the material and ideological foundations of the project.

Table of Contents

- Background

- Roots of the Janjaweed

- From Janjaweed to RSF

- Economics of a Militia

- Ideology of a Militia

- Agency and Violence

Background

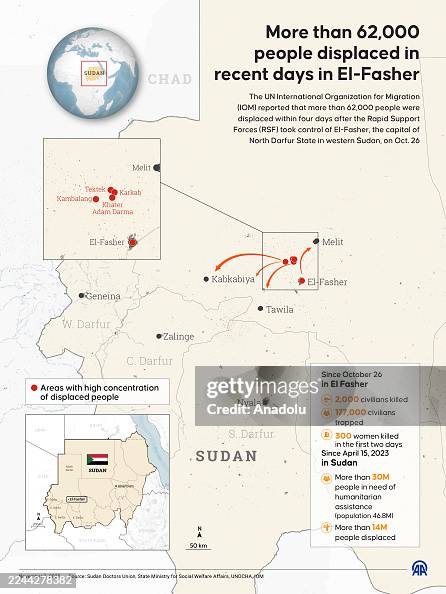

Sudan’s current violence did not begin with the RSF’s 2025 takeover of El Fasher, nor with the 2023 power struggle between the RSF and the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), the 2021 coup against the transitional government, or the 2019 ouster of Omar al-Bashir, or even the 2013 rebranding of the Janjaweed into the Rapid Support Forces (RSF). Its roots reach back to the 2003 war in Darfur—and further, to the 1980s, with the formation of the Janjaweed militia.

In 2003, Darfuri rebels rose up against the Sudanese government, due to systematic oppression of non-Arab communities. The Janjaweed militia became the backbone of the government’s counter-insurgency. Despite official denials, state resources flowed into Darfur, and the Janjaweed were equipped and coordinated as a paramilitary force, with communications gear and even artillery support (from the Sudanese Army).

Between 2003 and 2008, Janjaweed militias carried out crimes against humanity, ethnic cleansing, widespread rape, and torture in Darfur, killing an estimated 300,000 civilians and displacing about 2.7 million. These atrocities formed the basis for the International Criminal Court’s indictments of Sudan’s then-president, Omar al-Bashir, on charges of genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity.

The Janjaweed evolved into a formidable militia. Despite disarmament efforts, they were reorganized into the RSF, which grew strong enough to rival the national army. In 2023, this culminated in a power struggle between the RSF under Hemeti and the SAF under al-Burhan.

On 28 October, El Fasher—the capital of North Darfur—fell to the RSF, with mass atrocities, destruction, and rape reported. Much coverage filters Sudan through a humanitarian lens that catalogs harm and lists actors but rarely probes motivations or the political economy behind them, dissolving agency into an ethical abstraction.

This article takes a different approach. It examines the material foundations (land, resources, war finance), the ideological narratives (racial hierarchy, center–periphery identity, Islamist/Arabist frames), and human agency—why people joined, stayed, and acted as they did. It also challenges the reduction of Sudan’s crisis to “tribal warfare” or “Arab vs. African,” a framing that has justified excluding Darfur’s Arabs from engagement and has entrenched the very conditions that fuel militia violence.

References

- Entrenching Impunity Government Responsibility for International Crimes in Darfur

- Empty Promises

- Tens of thousands fleeing on foot amid atrocities in Sudan’s El Fasher

- All Eyes on Sudan

Roots of the Janjaweed

The Sudanese state’s “militia strategy” dates back at least to the 1980s under Jaafar Nimeiri and persisted through later regimes. In Darfur, many recruits were drawn from criminal bands and marginalized groups within so-called “Arab” tribes, then organized and armed. These militias also tapped cross-border mercenary networks in Chad and Darfur—some shaped under Gaddafi’s patronage and infused with Arab-supremacist ideas.

The Sudanese government funded and organized the Janjaweed in 2003 (and even before) to counter the Darfur rebellion after the regular army proved ineffective. The government did so despite clear evidence that these militias were committing severe human rights abuses, including forced displacement and widespread land clearance. Entire villages were burned on suspicion of rebel ties.

The British colonial administration had recognized dars (homelands) for most farmer groups in Darfur but left some nomad Arabs reliant on customary use rights—later strained by drought, desertification, and rising inter-communal violence. Some leaders then sought formal land for their people; others accepted promises of money and power, disregarding consequences. Not all Arab constituencies joined the „Janjaweed“; many tried to remain neutral, and a number of leaders refused to participate.

Over time, Janjaweed campaigns shifted land from largely settled farming communities labeled “African” to nomadic groups who, in a modern capitalist sense, were not traditional landholders. This dispossession created a lasting legitimacy problem: living on seized land demands continual force, outside patrons, and a steady flow of weapons to entrench and expand control. From afar, the conflict can appear as an “ethnic civil war,” yet victims included both groups marked as “Arab” and those marked as “African.”

Violence hardened identities: the more coercion was used and justified, the more communal labels were fixed and politicized, turning fluid social boundaries into rigid fronts. In this spiral, violence did not merely follow identity—it helped make it, as coercion and dispossession produced racialized boundaries that were then invoked to justify further violence.

Ethnicity has been manipulated by all sides, and lines have been sharpened by portraying the conflict as a genocidal war against “Africans.” Yet when government steps back and neighbors with long histories of coexistence meet to settle disputes, local politics and material interests outweigh imposed “racial” identities. Conflating „Janjaweed“ with „Arab“ helps perpetuate those narratives that seek to draw the conflict among tribal ethnic lines.

References

From Janjaweed to RSF

Mirroring the international conflation of “Arab” with “Janjaweed,” the Darfur Peace Agreement (DPA) signed in Abuja in 2006 left many nomadic “Arab” communities feeling betrayed. It sidelined their concerns and failed to address nomadic land ownership. With land at the core of the conflict, the agreement was seen as disadvantaging nomads and deepening distrust of the government.

The DPA called for disarming the Janjaweed. Yet nomadic groups—the backbone of many militias—have long fought to protect migration routes and, when necessary, force access to pasture and water. Fearing reprisals and lacking credible guarantees of security or land, many concluded that retaining their weapons was essential. At the same time, the Janjaweed had fragmented into multiple, often indistinguishable groups with overlapping interests, leaving the government unable to stop or disarm them.

Frustration among government-aligned militias simmered after 2006 and culminated in late 2007 with the mutiny of Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (“Hemeti”). Khartoum appeased him to prevent wider defections: Hemeti received a brigadier general’s rank and command, his men were issued military IDs and salaries, and a large cash infusion effectively turned his organization into a capitalist enterprise.

With Hemeti back on side, President Omar al-Bashir moved to reorganize Darfur’s militias under tighter control. In 2013 the government created the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) from the Janjaweed militias and put Hemeti in charge. The RSF was later granted regular-force status (2015) and incorporated as an auxiliary within Sudan’s armed services (2017), positioned in part to protect Bashir against internal coups. While the Janjaweed were renamed as the RSF, their tactics did not change and were used to crush uprisings in Darfur.

After mass protests in 2019, the army removed Bashir. Hemeti did not defend his former patron and acknowledged protesters’ demands as legitimate, but the RSF soon participated in violent repression, including the June 2019 Khartoum sit-in dispersal—echoing methods previously used in Darfur. An uneasy RSF–SAF power-sharing arrangement followed.

That alliance collapsed on April 15, 2023. General al-Burhan cast the RSF as bandits; Hemeti presented himself as pro-democracy. Beyond personal rivalry, the war reflects longer dynamics: the marginalization of Darfur, competition over economic and natural resources, and the state’s long-term use and arming of militias to quash resistance in the peripheries.

References

- Beyond ‘Janjaweed’: Understanding the Militias of Darfur

- Tribal Militias in Sudan

- Sudan’s outsider: how a paramilitary leader fell out with the army and plunged the country into war

Economics of a Militia

Initially intended as Bashir’s loyalists—as his legitimacy waned—the RSF was deployed nationwide under intelligence oversight to deter internal threats. In parallel, it assumed border-enforcement roles within Sudan–EU migration-control frameworks. That role was often opportunistic: units alternated between stopping migrants and trafficking or ransoming them—whichever paid more. Becoming Sudan’s border guard in chief proved an effective cover for smuggling.

The RSF and Hemeti understood that money and resources were the keys to power and loyalty in Sudan’s peripheries. He and his family built a financial empire behind the RSF, leveraging official clout to capture natural resources and state contracts. A turning point came around 2017, when his forces took control of the Jebel Amer gold mines in North Darfur. With Bashir’s approval, Hemeti’s firm gained export rights; soon a large share of Sudan’s gold trade was in RSF hands. Profits funded RSF expansion, enriched the Hemeti clan, and provided financial incentives for further recruitment.

The RSF also delivered geopolitical leverage. By deploying forces to Yemen in support of Saudi Arabia and the UAE—reports cited figures up to 40,000 by 2017—Hemeti secured external patrons. After Bashir’s ouster, Saudi Arabia and the UAE pledged $3 billion to back the army–RSF junta. The partnership extended to Libya, where in 2019 about 1,000 RSF fighters supported Khalifa Haftar’s offensive on Tripoli.

As Hemeti’s prominence grew, so did his business interests, aided by Bashir’s patronage. The family expanded into gold mining, livestock, and infrastructure, creating a revenue base independent of the regular state budget and the Sudanese Armed Forces. This autonomy strengthened the RSF’s bargaining position in Khartoum and in regional dealings.

The RSF also paid better than the army or other militias—a decisive factor amid economic decline after South Sudan’s secession, falling oil revenues, and gold’s rise as a pillar of the economy. For many young men in Darfur and beyond, RSF salaries, access to spoils, and protection networks outweighed scarce alternatives in a shrinking labor market. The scale of RSF-linked gold extraction even helped fuel a surge in gold flows to the UAE, underscoring the force’s economic reach.

As the RSF–SAF war unfolded, external finance remained central. Hemeti had become the UAE’s preferred partner, which sought to expand its regional influence through a proposed $6 billion port-and-agriculture project on the Red Sea coast announced in 2022, with Emirati firms holding a majority profit stake. Such deals fit a broader Gulf strategy along the Red Sea and offered the RSF prospective funding streams outside formal state channels.

As the war has progressed, the RSF has come to resemble the Bashir-era model: minimal pay for fighters and permission to pillage as de facto wages. This is not incidental. Revenue and coalition maintenance depend on the continuous appropriation of public and private resources. Such flows are largely immune to sanctions because they are sourced on the ground. Looting is also organized, not random.

In Wad Medani, the December 2023 raid on the World Food Programme warehouse—stocked to feed 1.5 million people for a month—was not the work of “hungry residents,” as the RSF claimed, but was organized by RSF commanders to provision their troops. Other plunder is more localized but still regulated: new recruits are encouraged to raid homes and villages as a form of payment for their participation in fighting.

RSF soldiers turned traders now sit at the intersection of predation and production. From influential positions, they broker the RSF’s new economic frontiers, taking lucrative cuts to keep goods moving. A reshaped social hierarchy gives the RSF an edge, enabling external alliances through labor and commerce—both as merchants selling to the public and as brokers moving goods to and within markets. Other occupations have been pulled into the same extraction-tied-to-production logic.

Five job types structure the RSF’s labor hierarchy: soldiers, informants, drivers, thieves, and day laborers. Recruits from tribes close to Hemeti sit at the top, serving as field commanders and economic entrepreneurs who manage markets and oversee supply chains.

References

- Beyond ‘Janjaweed’: Understanding the Militias of Darfur

- Sudan’s outsider: how a paramilitary leader fell out with the army and plunged the country into war

- Effects of EU policies in Sudan

- Money Is Power: Hemedti and the RSF’s Paramilitary Industrial Complex in Sudan

- The ugly side of the Africa-UAE (United Arab Emirates) gold trade: Gold export misreporting and smuggling

- All Eyes on Sudan

Ideology of a Militia

As the RSF–SAF war unfolded, external finance remained central. Hemeti had emerged as Abu Dhabi’s preferred partner as it sought to expand influence along the Red Sea’s key trade route, via a proposed $6 billion port-and-agriculture project with a majority Emirati profit stake. The deal fits a broader Gulf strategy on the Red Sea and promised off-budget revenue streams for the RSF beyond formal state channels.

Since independence, Sudan’s ruling elites drew on hierarchies that cast “Arab” as civilization and “African” as other. This framing helped justify unequal wealth distribution toward “Arab” elites in Khartoum, even as the country’s major resources lay in non-Arab peripheries—oil largely in what is now South Sudan, gold heavily in Darfur. The state, dominated by northern elites, sidelined Darfur and other provinces, while successive regimes in Khartoum—and allied currents in Libya—circulated Arab-supremacist and Islamist narratives that naturalized center–periphery inequality.

These ideas fed a national identity crisis after British colonialism: who belongs, on what terms, and which regions count as the country’s core. Peace processes—from the Darfur accords to the Juba Agreement—could not undo decades in which violence, marginalization, racialization, and centralizing rule decided who had access to land, protection, and revenue; many in Darfur felt excluded. As violence escalated, identities hardened, turning once-fluid lines between “Arab” and “African” into rigid identities.

Within this landscape, Hemeti and the RSF sought an ideological pivot. They recast themselves not as a militia born of repression but as spokesmen for neglected peripheries. In public statements—“a Sudan that belongs to all Sudanese… from Darfur to Kassala”—Hemeti styled himself a “son of the people,” rooted in the experiences of Darfur, Kordofan, and the East. The message targeted two audiences at once: peripheral communities long dismissed by the center, and external patrons looking for a post-Bashir interlocutor.

In an apparent attempt to echo the Sudanese revolution, the RSF brands itself as its continuation—a pro-democracy, anti-Khartoum-elite force promising to redirect wealth from the center to Darfur’s marginalized. Yet the branding is contradictory: in practice, Hemeti moves to replace Khartoum’s elites with his own clan, offering no program for governance—only extraction and short-term gain.

However, reports suggest that even Hemeti struggles to control the RSF’s Arab militia core. He now resembles Bashir decades earlier: maintaining a fragile coalition of militias with divergent aims that often clash with his own ambitions for a political career. Distinguishing opportunists from true believers is difficult. RSF operations have been largely extractive and looting-driven, with fighters stripping areas of resources and moving the spoils to Darfur or local markets—producing an ebb and flow of fighters at the front as profit opportunities shift.

References

- THE REPUBLIC OF KADAMOL: A Portrait of the Rapid Support Forces at War

- The Rapid Support Forces and Sudan’s War of Visions

Agency and Violence

This article traced the material and ideological foundations of the Janjaweed, from which the RSF later emerged. One question remains: agency. The Janjaweed and the RSF have been responsible for grave human rights violations for decades—so why do fighters continue to fight for them?

Hemeti built a capitalist empire that rivals Khartoum’s elites and used that wealth to finance the RSF. The loop is straightforward: the RSF secures resources; those resources fund Hemeti’s businesses; profits flow back into the RSF. This explains capacity and endurance but not the core question: how was the violence justified? A gun does not fire itself; roughly 100,000 fighters chose to join and remain. Pay and material benefits matter, but do they justify mass atrocities, rape, and the destruction of civilian life? While Hemeti’s family captured the revenues, most fighters saw them only as salaries, protection, and status—not ownership or control.

As economically profitable as the system created by the RSF is, it creates a political crisis for the RSF. The cost of keeping the RSF together is a sort of infinite expansion—one that is necessary to produce the looted goods and checkpoint taxes that sustain its payment system. This expansion means that the RSF is forever in crisis—always in need of new territory to conquer, and always at risk of its structure falling apart.

Hemeti presents himself and the RSF as champions of the oppressed against corrupt elites in Khartoum, yet the conduct of the war undercuts that claim. He is open about his business ambitions and his ownership of gold mines. After seizing large parts of Khartoum early in the conflict, the RSF left the city in ruins and did not attempt governance—signalling short-term extraction rather than a plan to rule.

To address the opening question of agency, there isn’t one sufficient reason. Affiliation brings privileges and protection that make continued association advantageous; what is taken by force must be held by force, so violence becomes self-perpetuating; violence also forges identities; social and command networks bind recruits to units; an ideology of dehumanisation lowers barriers to harm; and external funding and resource access reduce the need for local consent. Even together, these factors remain unsatisfying given the scale of the atrocities.

These factors may explain how the RSF machinery operates, not why its fighters, commanders, and supporters accept its actions. What could ever make atrocities on this scale understandable?

Read More

- Poetry as Resistance

- Christmas Market

- BDS: Resistance against Apartheid

- Antifa Ist International oder Er Ist Nichts

- Antifa Is International or It Is Nothing

If you enjoy our content, please subscribe to receive updates via email